You Will Also Forget, You Will Also Then Remember

On an artistic collaboration with photographer Laura Stevens

I’m grateful to the editors of The Mississippi Review, who selected this essay for their Art Issue, Volume 52, Issue 3, published February 2025.

This is a photo of a woman lying naked in bed. The bed faces a mantlepiece, to the left of which is a large, mirrored armoire, to the right a window you cannot see. The woman is turned onto her side, curled around something, curved, her face obscured. She is undressed, the sheets and the light from the window draped across her lower legs. At first, there appears to be only one figure in the photograph, this woman alone, her body seen twice: in the mirror above the mantle, and then, unexpectedly, in the mirror on the armoire door, angled to catch the dual reflections.

This is a photo taken by Laura Stevens, a British woman in her forties, for her 2023 exhibition at Paris’ Galerie Miranda titled “Tu oublieras aussi”—you will also forget. Her first exhibition, “Him,” was a series of male nudes, the men sitting or lying on a white bed, their bodies soft and decidedly feminine, displaying a shocking fragility: the curled-up flaccid penis, fluff of body hair, limbs contorted as if trying to hide or reach for something, someone, some version of themselves just beyond the viewer’s eye.

For “Tu oublieras aussi,” Laura asked women and couples to disrobe in front of her camera lens. The series is a sensual and cinematic meditation on intimacy, connection, and the quiet, secretive moments in between what is often a performance—of self, of femininity, of desire.

The woman in the photo is me.

There is a man in the photo, too, but that detail is of no importance.

* * * *

This is a photo of me and a man lying naked in a bed. He is wrapped in a sheet as if ashamed, or as if sleeping after sex. His face is hidden behind his arm, eyes closed. He is a bald head, he is a mummified body, he is a shape. A placeholder. He is a memory I once had. A body I had, too.

The photo is titled “Act Two.”

In “Act Two” I am lying naked on a bed, a man beneath the sheets beside me, my body curved against his, two parallel lines. Two sets of bent knees. Two types of prayer, two bodies facing different directions. My torso drapes across his sleeping frame. Head propped up on one arm, my expression is visible only in the mirrored armoire door—eyes downturned, face fallen.

The image shifts. Everything depends on something else. In the oval mirror above the mantle, the scene appears as if framed in a locket. A woman alone, because the man’s body is easy to miss. He disappears into the soft light, unimportant, forgotten, already gone.

Then you see his face and you remember.

In the mirror on the armoire door, you see my face and you remember. You remember what it feels like to fail to connect. To be a little disappointed. You remember the men who didn’t really try, who didn’t care enough, who lost patience. And how it feels to want more. How it feels to satisfy yourself when nothing else will.

The photo has a painterly light, like a Dutch still life from the sixteenth century. There is a softness in the way the scene is viewed. And the great mystery of the photo is how the bed, the mantle, the bodies, are so centered, as if viewed straight on. Where is the photographer?

(She is there, just out of the frame.)

* * * *

This is a photo of the truth: the truth is he was my lover but should not have been. The truth is we were not in love; no, the truth is I was hardly attracted at all. The truer love was between her, the photographer, and me, two friends trying to make a piece of art good enough for the walls of a gallery, walls that would host the photographer’s second show. The date already set. The art not yet made.

I had moved, earlier that year, to Paris, where I arrived to become the version of myself I dreamed of becoming. Where I ran away from a man who wanted me to become a version of a woman he had in mind, not my own. How do I know this? He gave me lovely, thoughtful gifts, like the first edition of Anaïs Nin’s 1972 chapbook Paris Revisited—but one of the last gifts he sent me off to Paris with was Literary Passion, the letters of Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller. He thought he was Henry, when, in fact, he was Hugo all along—willfully blind to who I really was, refusing to see my constant running away and running around. Henry, on the other hand, always knew what Anaïs was doing, and never asked for any type of monogamy or commitment. Their love was open, unpossessive. If this man who loved me had been the Henry Miller type, I would not have had to flee from him, breaking his heart in the process, to pursue my expat dreams, to become my real self.

I ran away to Paris. But I have not forgotten: how he loved me, and how much he failed to understand.

What is also true is that I came to Paris because of women artists. The French writers: Colette, Marguerite Duras, Simone de Beauvoir, Hélène Cixous, Annie Ernaux, Leïla Slimani, Virginie Despentes, Anaïs Nin. And the American writers who spent years here: Gertrude Stein, Natalie Clifford Barney, Sylvia Beach, Margaret Anderson, Djuna Barnes. I felt that these women, in particular the ones who wrote about desire, had some secret knowledge to offer me if I only could get closer to them, which meant learning French—a decades-long endeavor for which I’m only at the very starting point—and learning their culture, their feminism, their men.

I am often baffled by how a culture that birthed such powerful feminist writers and thinkers could also be so wedded to traditional gender roles and beauty standards. The women here in Paris with their lithe bodies, their effortless beauty that requires a great deal of effort, the way they are chained to femininity in its physical form. But their feminism seems to manifest instead in a casual approach to relationships, where infidelity doesn’t shatter one’s relationship or sense of self. From what I’ve gathered in my informal, first-hand research, the French have a slippery detachment to the trappings of relationships, in which marriage isn’t a hallowed institution and desire is something to court, and follow, at all costs.

* * * *

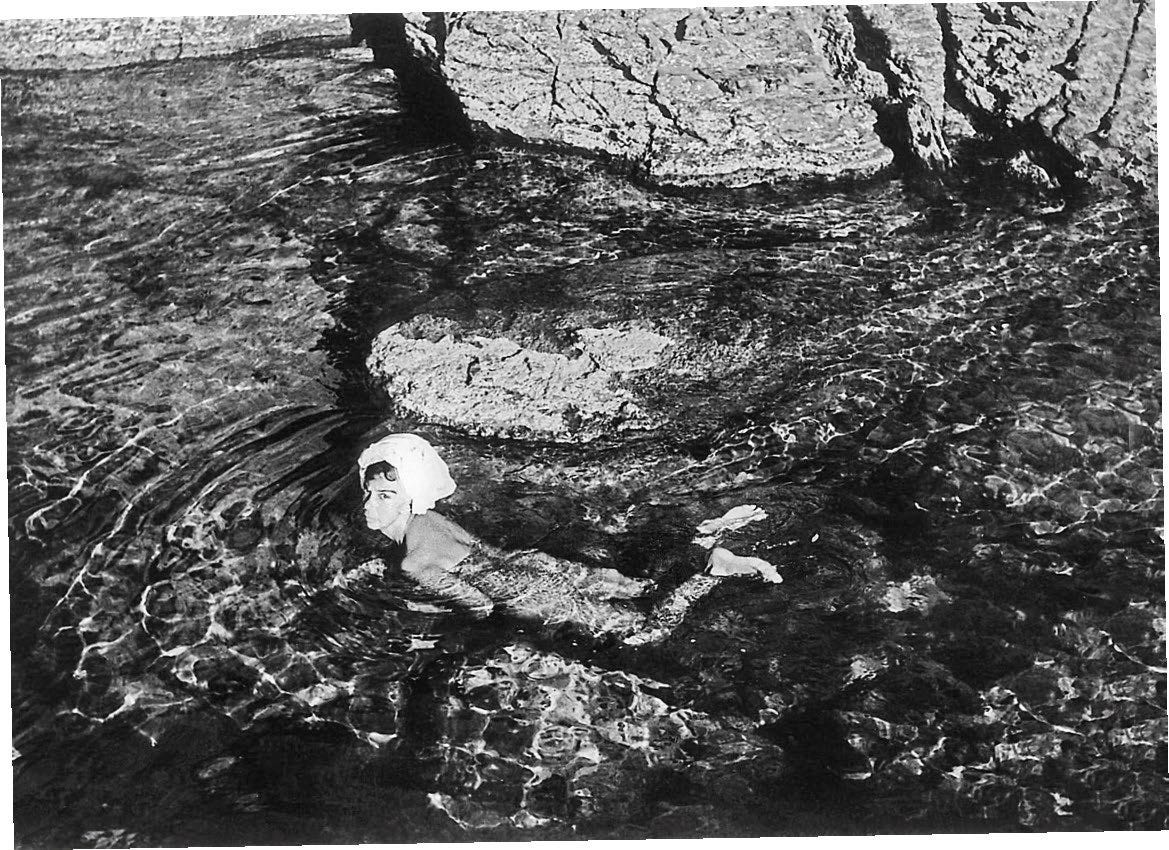

This is a photo of my friendship with Laura Stevens, how I undressed for her lens, followed her instructions. Our friendship solidified during my expat years in France, as we planned trips and art projects. In February, at the start of my second year in Paris, we came to her boyfriend’s country house specifically to each make our art. It was not our first time trying to get the right shot. The project had begun in Corsica the summer before, where Laura, her boyfriend, and I had traveled for an artist residency at a thirteenth century convent. In the turquoise Mediterranean Sea, in the crumbling walls of a convent where the Surrealist painter Leonor Fini spent her summers, I disrobed for Laura’s lens. I swam in a cove and tried to look ethereal. But that wasn’t it; we didn’t get the shot. I crawled atop Fini’s ancient stone pulpit, but that wasn’t it, either. Laura found a dead snake, took self-portraits with its corpse draped across her naked body, the symbolism bright red and burning.

In her self-portraits, Leonor Fini paints women with Medusa-like hair, dangerous accoutrements, a scorpion in a gloved palm. Breasts exposed, hair ablaze with candles, dripping with dark, seductive power. Her women sit on men, blithely unaware of the human furniture. Her women kneel at the open entrance between another woman’s legs, as if in worship.

I became obsessed with Leonor Fini’s art, with her summers squatting in the ancient crumbling convent north of Oletta, the costume parties and photographs of her and her artist friends, her multiple lovers, her fluid sexuality. We swam in the waters where she had swum, where she had been photographed naked, where I hoped her spirit would enter my own.

* * * *

This is a photo of Laura trying to capture something true in her art. I was trying to provide it. Nine months after a scorching summer week in Corsica, this time at Laura’s boyfriend’s country house in winter, with a man they had introduced me to, their friend. We were all together for the weekend, two couples, four artists, to create.

The first idea was a photo in the pond. I disrobed and waded into the freezing February water, my hands turning hot with icy pain. But that wasn’t it.

The next day we tried again. I waded in once more, this time with the sun low behind my back. I slipped my hair beneath the frigid water and hunched against what hurt. I followed Laura’s instructions to try less for beauty. To aim for animal instead.

And here is where we first hit the spark of what Laura was looking for. She had something, now.

In this photo, which also hung on the walls of Galerie Miranda, I am submerged in a pond to my waist, my naked back and right breast exposed. My hands hidden in the water, hair wet and red in the setting sun. Facing away from the camera, looking down. The water ripples around me like a dress fanned out. The leafless trunks of trees are reflected in the water behind me, as if the world were upside down. It is a cold scene, dizzying in its shapes and circles, and of what? A woman halfway in. Or halfway out. A woman with her back turned.

To me, it feels monstrous. I appear in the frame like a kind of female creature unexposed. As if in a private moment but having nothing to say.

It is the other photo that captures the truth.

After the success in the pond, we tried in the bedroom. This time the man, my lover, was willing to disrobe, too. In fact, he wasn’t shy—a musician himself, he was eager to help Laura make her art. We tried in two bedrooms, Laura stood outside two windows, looking for something unknown to emerge. We did not kiss in front of her lens, but arranged our bodies like strangers would, shyly and without love. But we knew each other’s bodies already. What we revealed was how little we knew each other, the truth of all our lies in the dark.

* * * *

This is a photo of the first time I let an artist photograph me naked. But I remember the men who tried. There was one, a sculptor, for whom I had worked as a nanny. We collaborated on an art project, two large journals in which he drew or I wrote poems, exchanged every other week for the duration of one summer. We read Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse and discussed desire. He was married; I was twenty-five. He wanted to draw me nude but I declined, afraid of what prowled beneath the surface. Afraid of being asked to go too far. I had only slept with two men. His wife was a friend. But also, though I was curious to see how I might appear in his lines, his graceful nude women arching across the pages of our notebooks, I did not desire him, and so I did not desire to fully expose myself for his art.

Out of our collaboration, I wrote a chapbook of poems. He made a mixed media painting that later hung in a gallery, a large canvas covered in bright paint, with a small sculpture of a woman at the bottom. He also gifted me a smaller version, a diptych made of two pieces of wood, on which two nude women float in a sea-green ocean of paint. My words, written in his scratchy handwriting, stretch across both pieces: “She could feel this,” and “this distance within.”

Fifteen years and fifty men later, I was ready, finally, to disrobe for the artist’s eye. But only a woman’s. Only a friend. There had to be love there, and trust. A love I had now, for myself. A trust I had in her art, her eye.

The image shifts. The one you have of yourself, I mean. It was so easy to disrobe for Laura.

* * * *

This is a photo, along with thirteen others, in a show titled “Tu oublieras aussi”—you will also forget—words tattooed on Laura’s boyfriend’s arm, words that, according to Casanova’s memoir Histoire de ma vie, his lover Henriette etched on a hotel window using the edge of a diamond, before leaving suddenly, without explanation. She knew she would be forgotten, yet Casanova, writing his memoir, calls her the greatest love of his life. She knew she would be forgotten, but we remember, still, her words. The myth of her.

One of the ways we fight against the disappearance of the self—by which I mean the fact that we will die—is by having children. Another way is by making art. Scratching messages of our desire and our longing into windows, walls, and pages, the mirrored surfaces of life.

“She could feel this distance, this distance within.” And “You will also forget.” Words by women, written in the memories and art of men.

But words are often not enough. How do I explain with words that there are many women inside me, that my sexuality has been so shaped by pornography, voyeurism, and taboo that I no longer know what or who I desire? That I am so skeptical of what sexual desire even is, how long it lasts, if it’s ever true, that I sleep with men I don’t desire?

It is because I am two women: the one who dreams and fantasizes, and the one who long ago learned to appease, flirt, and lie, to use my body and beauty as tools.

I learned to become two women. To court the space within myself, not ask for much. To pretend. Maneuvers which have kept me safe for all these years.

* * * *

This is a photo of two women: there is the woman in the mirror, who appears to be holding her lover, and across the space of the photograph, there is another woman, whose expression reveals her sadness. You see her face and you remember. That this has also been you, your truth, your dissatisfaction.

Laura Stevens set out to capture desire and intimacy, couples in their most tender moments. Wanting. Touching. And she did photograph some couples in love; their images do tell that story. But in the end, what appears in “Tu oublieras aussi” is a story about desire and intimacy interrupted. The honest, secretive moments you hope the lover doesn’t see. She has captured a truer story, perhaps more common than being in love, more tedious, more real, about women’s inner lives and sensuality—women viewed by a female gaze. The result is not a hyper-aroused or aggressive depiction of our sexuality, but one marked by disconnection, solitude (even in someone else’s presence), and turning away.

In the photo where I am alone in the pond, my face is turned away, hidden from the viewer’s eye by dripping hair. In the other photo, where I am not alone, my face is also turned away, my closed expression caught only by the particular angle of the mirror. The viewer is privy to something very private, something they should not be seeing at all.

There is a man in the photo, too, but that detail is of no importance.

Then you see him and you remember.

There are so many times I gave myself away without intending to. So many ways I betrayed myself, so many bodies that collided with my own and only took. I learned to allow the taking. And then I learned to take my own. To find in myself an anchor. I became the kind of woman I dreamed of becoming: one who writes, who moves to another country, who is alone, who is not a mother, who leaves, who loves many men, who disrobes and steps into the cold February water one more time if it means more art. If it means more art from a friend I love, who has helped me become this woman because she is, too.

* * * *

This is a photo of me. There is a man in the photo, too, but he hasn’t touched me, not in any real way. I have forgotten him already, or I will soon enough. The look on my face could be described as forlorn, or wistful. Certainly a little sad. But not despairing, not giving up hope. Unsatisfied, yes, but ready to move on. This is a photo of me that shares all my deepest secrets with the world. That shows a kind of distance, the distance harbored within my psyche, untold except for what is shared in art. And only a woman’s lens, only Laura, who is in the photo, too, just out of the frame—only she could have understood, and unearthed, this truth of what a woman gives away, how we lie, and how deeply we desire something more. What we forget, and how we try to be remembered—etching our name into the mirror, arranging our photographs on the gallery wall, writing our words on the page, before we leave, before we set off, willing to expose ourselves in search of our own truth, to follow where female artists lead, have always led, the way.

Yet again beautiful and courageous. In some ways you are my Laura 🙂

You hide your sadness well, you've made it an art form <3